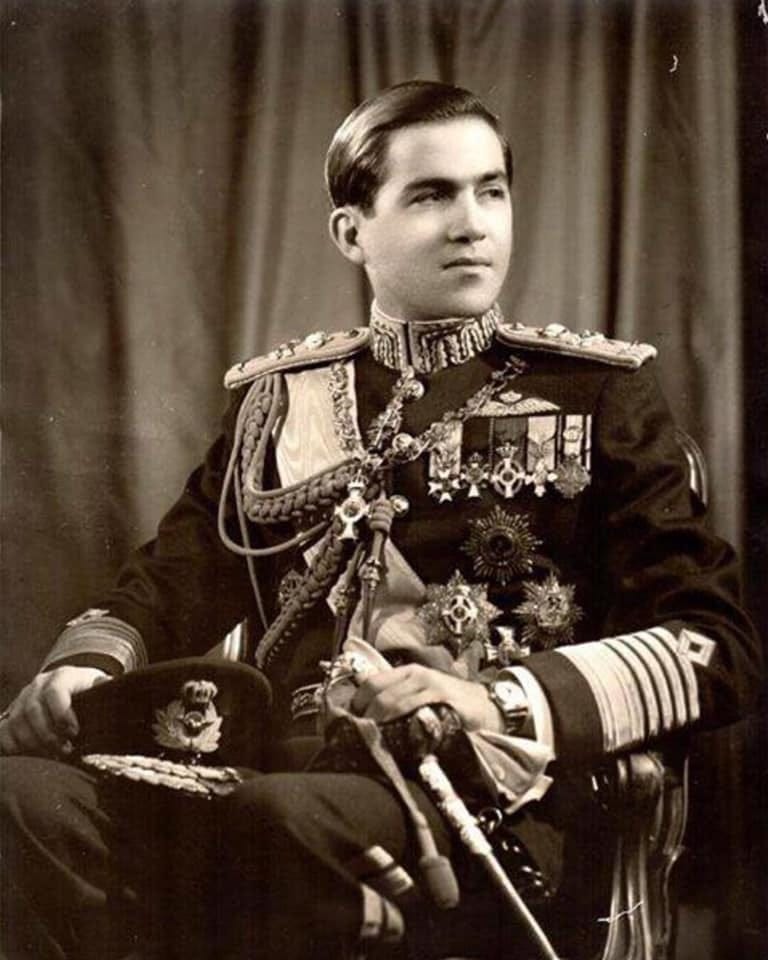

Constantine II, King of the Hellenes, 1940-2023

A man of good intentions, and an accomplished Olympic athlete, but a monarch of limited political acumen

King Constantine II, the last king of modern Greece, passed at the age of 83 at a hospital in Athens in the early hours of January 11, 2023.

Constantine was born four months before Greece was invaded by fascist Italy on October 28, 1940. He and his family sought refuge in the British-ruled Middle East and, eventually, South Africa. Following the end of the Nazi occupation of Hellas in October 1944, he and his family returned to the Homeland. His father, Paul, acceded to the throne after his brother, King George II, died in 1947. Constantine succeeded his father in October 1964, who passed after a short illness at age 63.

From the get go, Constantine, who was 24 at the time of his coronation, faced an intractable political situation. Greece was awfully poor and wracked by political infighting between communists and “democratic” socialists. The then prime minister, George Papandreou, an octogenarian, was leading a left-leaning administration struggling to control a perennially turbulent country that had emerged from a bloody communist insurrection only in summer 1949.

Papandreou, an old school Venizelist republican, wasn’t exactly an “anti-royalist” but, having cut his political teeth under liberal Eleftherios Venizelos, modern Greece’s most prominent politician, he was determined to limit the throne’s “interference” in government operations and he was soon at daggers drawn with the palace over the appointment of a defense minister. But, unbeknownst to both Papandreou and the king, a cabal of army officers was already putting the finishing touches to a coup d’etat to “save” Greece from (a non-existent) communist threat.

The putschists struck in the early hours of April 21, 1967, dissolved the Papandreou government, sequestered all prominent politicians (including an already ailing Papandreou), and arrived at the palace to seek the king’s endorsement, which was reluctantly and implicitly offered under the “persuasion” delivered by armor and heavily armed military patrols throughout Athens.

Constantine, at the age of 27, was hardly an astute politician and Greece in 1967 was more of a haphazard street-violent zoo rather than a “modern” democracy. With the army in firm control, and with thousands of bona fide “democrats” in jail and/or en route to internal exile, the young king was literally blind and deaf regarding the confused, slapdash, and often violent Hellenic politics.

Nevertheless, Constantine was determined to show the insurrectionists who was the boss and got some senior army officers, unhappy with the putschists, to begin planning a countercoup.

The latter was launched in mid-December 1967 and failed miserably thanks to Papadopoulos exercising tight control of the armed forces and possessing up-to-the-minute intelligence on who was working with who to undermine the junta. Within hours of this failed attempt, centered in Thessaloniki, Greece’s second largest city, Constantine and his family were on their way to a head-over-heals exile in the Italian capital.

The fall of the junta in the summer of 1974, after the catastrophic Turkish invasion of Cyprus, did not automatically result in Constantine’s return to Greece. Antiroyalist sentiments remained deeply rooted among Greek voters and Constantine Karamanlis, a former conservative PM, who was forced into self-imposed exile after the Greek Left denounced the 1961 elections, conducted by his government, as fraudulent and the product of a manipulative and illegal “Karamanlist parastate,” returned triumphantly to Greece, on July 23, 1974, to fill the political vacuum created by the junta’s precipitous collapse.

Karamanlis, it turned out, was a “crypto antimonarchist,” who had clashed with Constantine’s parents during his last premiership before the junta. Amid the chaos triggered by the Turkish piratical invasion of Cyprus, Karamanlis moved quickly to defeat any attempt to restore the monarchy although he had initially appeared agreeing to Constantine’s reinstatement. He won the October 1974 elections by a landslide, which allowed him to form a bulletproof administration and declare Greece a republic.

The fall of the monarchy was sealed via another referendum, later in 1974, that resulted in a majority vote against Constantine’s return to the throne. Constantine & family had to settle for staying away from Greece as itinerant royals.

With the passage of time, however, the royal family reconnected with Greece albeit in a halting and legally tortuous way. Consecutive governments did their best to severe Constantine’s links to the country by way of legal constraints that included, among others, the punitive confiscation of all royal properties. It was not until 2013 that Constantine and his spouse, Queen Anne-Marie, were allowed to return to Hellas and purchase property that became their permanent residence until they relocated to Athens in 2022 due to the former monarch’s sharply deteriorating health.

The former King’s passing offers the perfect opportunity for yet another cacophonous slugfest between Left and Right—with the former demanding the least possible funereal honors for King Constantine and the latter twisting her own scanties over wanting not to tease the communists with a cattle prod as elections loom, most likely, in the spring.

“Dependable” history on anything begins to appear after all protagonists of a given era have passed into eternity.

This is hardly the time for an honest appraisal of what the monarchy did, or didn’t do, in pursuit of Hella’s best interests—a subject that has never been approached by a truly level-headed Greek historian, with very few honest, but unsuccessful, exceptions (who remained always cognizant of the ugly and vituperative howling of the Left).

Modern Greeks are too argumentative, mean-spirited, and prone to bursts of hostility when it comes to the dikaia (rights) of a blood-drenched, convoluted, and tortured country and people like Hellas.

Perennially divided, and hostile to one another, Greeks continue to pay the price of primitive vendettas and clueless puppet show politics. Constantine’s passing will thus offer yet another opportunity for a punch-up between two equally deaf-dumb-and-blind opposing lineups.

In the end, as a Greek popular saying reminds us, “Only he who passes is finally free [of all earthly afflictions].”

King Constantine is now free forever.